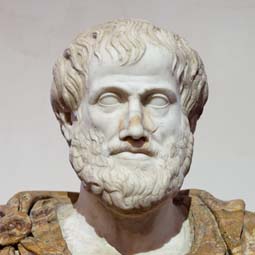

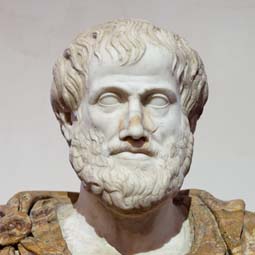

Among the theoretical sciences investigated by Aristotle, natural philosophy and metaphysics are the most universal. He explores these topics in his Physics and Metaphysics. Here, I'll attempt to give a brief summary of some of Aristotle's most important ideas in these areas.

From his predecessors Aristotle takes the idea that there are four basic elements: fire, air, water and earth. But Aristotle develops a new explanation for the distinctions between them. On his view, the physical world is a continuum capable of exhibiting various attributes, and the four elements are determined by two pairs of opposing attributes: wet - dry and hot - cold. Fire is hot and dry whereas air is hot and wet. Water is cold and wet, and earth is cold and dry. A number of observations fit nicely with this theory, particularly the condensation and evaporation of water. The world is further finite and spherical in shape, as it is most notably in the philosophy of Parmenides, and the physical world admits of no vacuum.

While a vacuum is an integral part of atomistic theories as the space between atoms, it is impossible to describe consistently within the framework of Aristotle's theory of substance, which is based on the interdependence of form and matter. On Aristotle's theory, whatever exists is a combination of both form and matter. Matter cannot exist without form nor can form exist without matter. Since a vacuum is defined as a place devoid of matter, a vacuum thus cannot exist. Being devoid of matter, it would necessarily also be devoid of form and hence of any being whatsoever.

In his Metaphysics, Aristotle examines in greater detail the relationship between matter and form

as well as the relationships between the various formal properties of that which exists ("being"). While Aristotle

does maintain the primacy of form over matter, the dependency of form on matter is his main critique of Plato's ontology, according

to which form is the only true being. In Plato, the material universe exists only as an inferior imitation

of the forms as they exist in the immaterial world of Ideas. While Aristotle's view that substance

is form clearly draws from Platonic doctrine, his insistence that form can exist only

in conjunction with matter marks a radical departure from Plato's teachings.

In his Metaphysics, Aristotle examines in greater detail the relationship between matter and form

as well as the relationships between the various formal properties of that which exists ("being"). While Aristotle

does maintain the primacy of form over matter, the dependency of form on matter is his main critique of Plato's ontology, according

to which form is the only true being. In Plato, the material universe exists only as an inferior imitation

of the forms as they exist in the immaterial world of Ideas. While Aristotle's view that substance

is form clearly draws from Platonic doctrine, his insistence that form can exist only

in conjunction with matter marks a radical departure from Plato's teachings.

According to Aristotle, substance is form, which in general can only exist when combined with matter. But material things have all kinds of different attributes contributing to their forms. Dogs, for example, have different breeds, colors, sizes but are all still dogs. On Aristotle's view, some of a dog's attributes make up its substance and others do not. Color and size, for example, are attributes that are not in the category of substance whereas "animal," "mammal" and "dog" are. We may note that these concepts can be organized hierarchically from general to specific. In the case of living things, this hierarchical organization forms the basis of the classification scheme still used in biology.

So, the form of any particular thing has an internal structure, with concepts of substance having priority over other descriptive attributes. The most specific possible substance describing a being is the essence of this being. Aristotle's extant works leave sufficient doubt about what essence is exactly that this issue has remained controversial. Some interpret Aristotle to mean that there is an individual form associated with a particular being and that that form is its essence. For others, the essence of a dog is simple "being a dog," so that one dog's essence is the same as another's. I don't intend to attempt to address this difficult interpretive issue here, but since essence is one of the central concepts in Aristotle's ontology, I feel that this controversy does need to be mentioned.

What does need to be addressed is the way in which Aristotle's notions of potentiality and actuality relate to essence and substance. Potentiality is closely related to Aristotle's view of matter. As noted earlier, the four elements are defined according to the particular state (hot or cold, wet or dry) of undifferentiated matter. Matter with no attributes at all--which would be matter without form--doesn't exist at all but only at minimum with the fundamental properties of hot or cold and wet or dry. In turn, the four elements form the material for certain, more complex beings, such as different types of stone. Out of these stones, one can then build houses. At each of these levels, we see one (relatively) unformed group of things put together into a certain form, which may in turn be the material for a structure or form of a higher level. Earth, in some mixture with water, air, and possibly even fire, is formed by various natural processes into marble, which human beings may use further as the material for a building. Whatever the particular elemental ingredients of marble might be, they have the potential to become marble if they are combined in a particular way. And the marble, together with other necessary materials has the potential to become a house. This potential is then actualized when the elements actually become marble and the marble actually is formed into a house.

The potential inherent in matter is thus actualized when the matter takes on a particular form. So, how does matter come to take on the form defined by a substance concept? While Aristotle's views on this subject can be applied to inorganic matter, they can be most easily explained in biological contexts. Here, we begin with reproduction, in which the parents contribute form to an initially unfertilized egg. This form specifically does include the substance of the progeny in the sense of a specification of its species, whether that be a grapevine, and olive tree, a dog, or a human being. So, there is a transference of essence to a certain material, namely the egg or seed. What now happens is that the essence causes this seed to grow in a particular way, or to strive to achieve the form with which it was imparted. With living things, their essence can be seen to form a final cause, which the particular being then strives to attain.

While we have only scratched the surface on some of the central issues of Aristotle's physics and metaphysics, we have now at least touched upon some of the most important points. First, Aristotle departs from Plato's view of form when he postulates the interdependence of form and matter. Second, within the collection of attributes that something has some of these attributes make up its essence. Third, the essence defines a teleological final cause which defines the inner transformations which the being will invariably undergo of its own accord unless hindered by external intervention. So, we have been able to touch upon Aristotle's critique of Plato as well as some central aspects of his teleology and theory of change.